Notes on excerpts from Walden, by Henry David Thoreau

Carl Bode, in his introduction to Penguin’s The Portable Thoreau, discusses Thoreau’s inheritance from Emerson but he is careful to distinguish Thoreau’s distinction and departure: “ . . . he followed Emerson in his bold allegiance to the individual instead of the group and in his emphasis on respecting one’s inner bent. In fact he taught [Emerson] the full meaning of ‘self-reliance.’ And he surpassed Emerson in his Transcendental enthusiasm for nature in any guise. It is true that nature itself later became to Thoreau less of a deity and more of a collection of detail; but even nature just as scenery afforded, he always thought, the ideal setting for bringing out the best in people” (17).

In this passage, Bode suggests that a person’s sense, or intuition or insight, comes from within that person, and in nature one can better come into contact with that internal sense of self (as Bode says, “the ideal setting for bringing out the best in people”). If we think about this kind of relationship to “nature,” what role does nature play for the person? Is it a service role, a role that is contributive rather than significant in its own right, as in “nature for nature’s sake” (not for what it can provide to man)?

In light of the above – regarding the idea of self-reliance (despite however much the phrase has become overused) – we considered this passage from Walden in class: “I know of no more encouraging fact than the unquestionable ability of man to elevate his life by a conscious endeavor. It is something to be able to paint a particular picture, or to carve a statue, and so to make a few objects beautiful; but it is far more glorious to carve and paint the very atmosphere and medium through which we look, which morally we can do. To affect the quality of the day, that is the highest of the arts. Every man is tasked to make his life, even in its details, worthy of the contemplation of his most elevated and critical hour” (343). To find this kind of deliberative hour, Thoreau went “to the woods.”

Greg Garrard, in his text Ecocriticism, addresses Walden, alerting us as readers to the status of the text as a “transitional work” (52). Employing the ideas of critic Lawrence Buell, Garrard writes that “Walden is at the midpoint of a movement from youthful anthropocentric transcendentalism to the mature biocentric perspective revealed in the late essays on wilderness” (55). Biocentrism, then, focuses on biota rather than on the human. Thus Walden signals a move towards what I above called “nature for nature’s sake.”

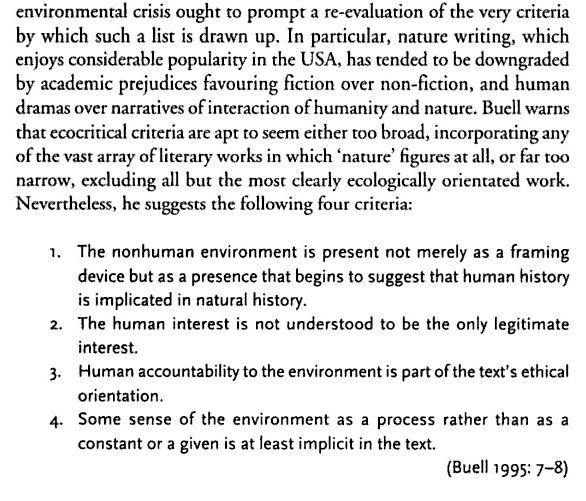

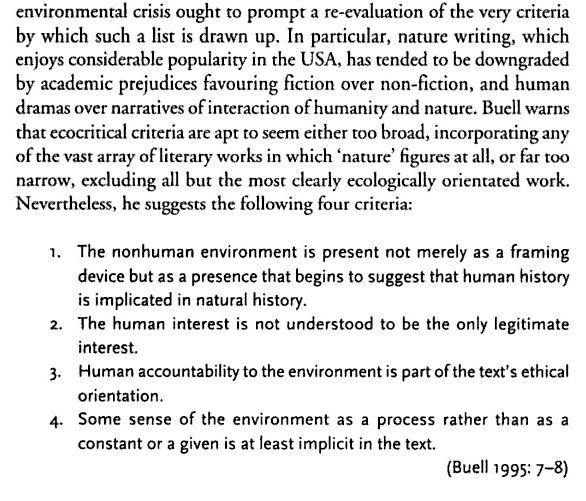

Taking a view across a broader horizon, Garrard identifies the lionization of Thoreau within the canons of American nature writing and American literature more broadly. Yet, via Buell, Garrard points out a certain “prejudice,” despite the popularity of a non-fiction account like Walden, against works of non-fiction that put “human dramas” on the sidelines. More specifically, Garrard reports Buell’s assessment that people would prefer to read a text where the human and human dramas take center stage rather than a text where nature’s realities, problem, or “dramas” are the central focus. This is a problem for Buell and thus he argues that the “lists” that constitute our canons of reading should be reconsidered. Buell argues that (and what follows is a passage from Garrard’s book) an:

Such parameters of assessment would allows texts both fiction and non-fiction, and those more recognizably “biocentric,” to be increasingly established within the canon of “nature writing,” a genre that we can see as needing a different name.

So, we have many difficulties emerging here, included among them the role of the natural place within the work of literature and the role of the person in that place, or the role of the person (or collectives of people) as writer (or writers). Buell tries to set up a structure that we can use, “ecocritical criteria,” that will help us to determine whether a text is “ecological” or simply a text that features a place in a non-vital role, as a sidelight to the central dramas of the human.

In class, we touched upon many themes, among them the legacy of Thoreau’s Walden and the various misapprehensions (and perversions) of the kind of self-reliance it discusses. We discussed briefly John Krakauer’s Into the Wild, and the film version of it, and we also discussed the television program Survivorman, which perhaps also inherits from Walden but takes a survivalist rather than a co-existence type of approach to “natural” places. We quickly discussed the references to civilization and “savagery” within Walden and we also noted Thoreau’s references to the increased mechanization of New England culture in the mid-nineteenth century (and more largely, of American culture and beyond). We discussed some of the privileges that Thoreau elides in his discussion of embarking on an experiment such as his (more specifically, what types of people during his time might not have been as able to undertake such an experiment). Finally, I mentioned the critical approach called “ecofeminism,” an approach to textual interpretation that examines the subjugation of the natural world as analogous to the historical subjugation of women and/or other marginalized or disadvantaged groups of people.

Regarding the “cult” of Emersonian “self-reliance,” you might want to look at a recent article from The Chronicle of Higher Education:

http://chronicle.com/article/Giving-Emerson-the-Boot/63512/

The comments are especially interesting.